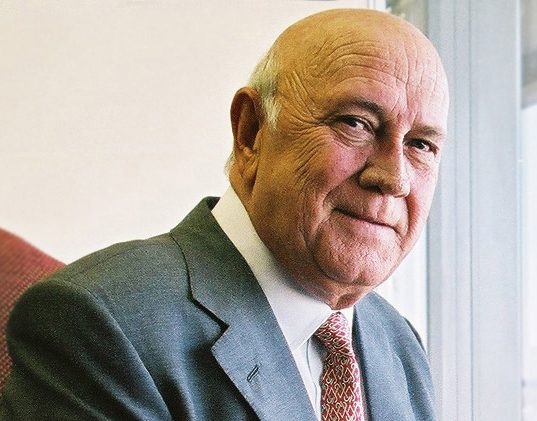

The death of South Africa’s last apartheid-era president Frederik Willem (FW) de Klerk this week has divided opinion in the country, with some praising him for his decision to end the reviled apartheid system and others refusing to accept he died a changed man.

De Klerk, who ruled South Africa from 1989 to 1994 and later served as deputy president from 1994 to 1996 under the country’s first black president Nelson Mandela, died on Thursday after losing a battle against cancer.

He was jointly bestowed with the coveted Nobel Peace Prize with Mandela in 1993 for his role in agreeing to dismantle the racist apartheid system that promoted racial segregation and “separate development” for black and white South Africans.

His death was received with shock and sadness by some, including President Cyril Ramaphosa and former president Thabo Mbeki.

Ramaphosa said de Klerk played a vital role in South Africa’s transition to democracy in the 1990s, “which originated from his first meeting in 1989 with President Nelson Mandela who was a political prisoner at that stage.”

“He took the courageous decision to unban political parties, release political prisoners and enter into negotiations with the liberation movement amid severe pressure to the contrary from many in his political constituency,” Ramaphosa said.

The Thabo Mbeki Foundation praised de Klerk for choosing “to accept the reality that it would be futile to continue to defend the apartheid system and he played a part in paving the way for the democratic transition in South Africa.”

“Mr de Klerk’s passing should thus serve as a moment for all South Africans to reflect on what it is we need to do to complete the journey to which we committed ourselves in 1994, of building a non-racial, non-sexist, democratic and prosperous country that truly belongs to all who live it,” the foundation said.

But de Klerk’s role in the transition to democracy remains a highly contested issue, with black South Africa unhappy about his failure to curb political violence in the turbulent years leading up to the 1994 multi-racial elections.

Although he won the Nobel Peace Prize, de Klerk never took responsibility for the violence perpetrated by security forces under his leadership.

As expected some of the most vocal criticism came from the militant opposition Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) which has threatened to oppose “a state funeral for a man who died without accounting for the blood on his hands.”

“To honour de Klerk with a state funeral would be to spit in the face of gallant liberation heroes who suffered in his hands and had their children murdered in his quest to stifle the freedom of black people,” EFF said in a statement.

It said a state funeral for the former president would be an insult to many families and communities who lost loved ones and “were maimed by his state-sponsored black-on-black violence.”

Other critics included political analyst Sipho Seepe who refused to accept de Klerk’s posthumous apology that was aired in a video released by his family after his death on Thursday.

Moments after confirming his passing, the FW de Klerk Foundation shared a video of the 85-year-old’s last message to citizens in which he said his views on apartheid had changed significantly since the 1980s.

De Klerk apologised for the damage which apartheid caused to non-whites, and said the apology was not only in his capacity as the former leader of the National Party, but also as an individual.

Seepe said de Klerk’s apology would not erase the fact that thousands of South Africans and people from neighbouring countries died under his watch and that after leaving office the former president never championed reparations for the damage that had already been done.

“To say you are sorry is fine, but it does not sanitise or change the course of history,” Seepe told journalists.

Funeral arrangements would be announced in due course.

JN/APA