It is more than a year since a controversial swap deal with the self-proclaimed republic of Somaliland nearly delivered Ethiopia access to a port on the Red Sea coast.

In exchange Somaliland would have been recognised as a sovereign republic by Ethiopia, a prospect causing tension with Somalia which sees the enclave as part of its territory and frowns on any attempt to treat it as an independent entity in violation of its territorial integrity.

15 months later the ‘port-for-recognition swap’ is all but aborted and the battle lines are drawn. At the crosshairs of the tension was the Red Sea and its place in the geopolitical chessboard pitting several Horn nations against Ethiopia’s maritime goals.

The stakes could not be higher with a web of alliances among Red Sea riparian states being forged to neutralise their landlocked neighbour’s desperate quest to exert dominance in the region and give its global trade a much needed fillip.

The Red Sea, covering a surface area of 438,000 km2 and straddling six countries in Africa and the Middle East is strategic to trade, security and other connections to the outside world which Ethiopia desperately covets to the consternation of its coastal neighbours who see it as their exclusive preserve.

This body of water has Yemen and Saudi Arabia constituting its eastern shores, while Egypt, Sudan, Eritrea, and Djibouti straddle its Western maritime boundaries.

Somalia through its Somaliland territory also lays claim to some coastal stretch of the Red Sea and has been left scrambling for the right response since Ethiopia’s passive aggression to secure a port for its burgeoning trade.

A new book released in March 2025 entitled Ethiopia’s Red Sea Politics: Corridors, Ports And Security

In The Horn of Africa by Dr Biruk Terrefe interrogates the nature of development economics in a volatile region where aggressive pursuit of geopolitical interests dictate foreign policies.

The book which is the product of a research explores ”the relationship between infrastructure and

state-building, particularly how large energy, transport and logistics systems have shaped (and

are shaped by) political orders and overlapping sovereignties, especially in the Horn of Africa”.

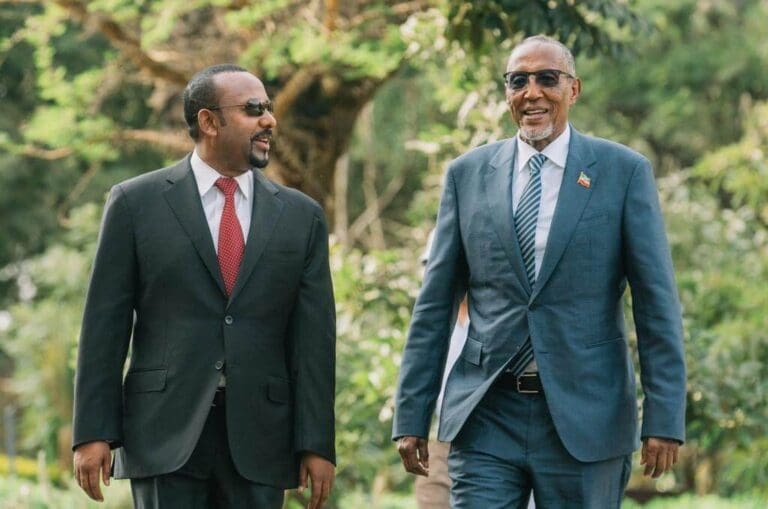

Dr Terrefe, who doubles as a lecturer in African politics at the University of Bayreuth and a Research Associate at the African Studies Centre at Oxford University in his introduction to the book recounts how in October 2023, Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed gave his ‘From a Drop of Water to Sea’ speech to parliament that sought to rip into shreds a generic understanding of the nature of the region’s political economy.

Dr Terrefe’s book quotes PM Ahmed’s doctrine as arguing that ”the world’s most populous landlocked country should no longer depend on bilateral arrangements and the goodwill of its

neighbours to import and export goods. Ethiopia has an explicit desire to gain direct access to

the sea”.

Abiy’s lecture painted a picture of an alternative model that would create serious political ramifications for the region, presenting a broader vision of Ethiopia’s place in the world of the 21 century.

Egypt joins the fray

For the past few months a flurry of diplomatic offensive has been gathering pace in the Horn of Africa where the endgame appears to be unfettered access to the Red Sea as the ultimate prize.

Eritrea, Egypt, Sudan and Djibouti have been finding common cause to fend off Ethiopia, which is fast turning into a regional pariah given that a few nations are ready to entertain its drive for an outlet to the sea.

The timing of a visit to Cairo of Eritrean foreign minister Osman Saleh to hold talks with Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi provides a window to understanding how Ethiopia’s neighbours view its designs and how they were being thwarted.

Eritrea had fought a bitter two-year conflict over territory with Ethiopia which ended in 2000 and although both countries recently said they are in no mood for another war, their diametrically opposed geopolitical positions could drag the region into the precipice, Saleh warned.

Sisi and Saleh dilated on the situation in the Horn of Africa and ways to enhance stability in the region, either through the joint efforts of their two countries or through the trilateral coordination mechanism with Somalia.

It was emphasised that Egypt and Eritrea would remain committed to supporting Somalia in not only combating al-Shabaab but preserving the country’s unity and territorial integrity.

The inference was clear. The entente cordiale between Eritrea and Egypt aside from working towards restoring peace to war-torn Sudan would protect the Red Sea and reject the involvement of a non-riparian country like Ethiopia for which access to the sea is an existential imperative.

The Horn of Africa is a region prone to long running disputes between Ethiopia on the one hand and Eritrea and Somalia on the other. These states considering themselves militarily weaker than Ethiopia have been looking to Egypt for diplomatic and military support. The results are a series of defense pacts with Cairo to prepare for a worse case scenario or as a deterrent should Ethiopia decide on a militaristic approach. Eritrea’s foreign affairs minister Osman Saleh had warned against Ethiopia’s ‘insidious’ plan which runs the risk of sending the region tumbling down the slope toward conflagration.

Since 2011, tensions have been simmering between Cairo and Addis Ababa over the building of a controversial dam on the Nile River, which Egypt says drastically reduces its historical share of water from the world’s longest river. Ethiopia denies this and claims the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), the largest hydroelectric power facility in Africa was to meet its energy deficit and that of the region with no adverse effect on the volume of water reaching Egypt from the Nile. The unresolved row despite several mediation attempts has given rise to periodic rumours of going to war with both countries never ruling this out. Egypt therefore

Ethiopia which lost its position as a riparian nation following Eritrea’s secession and automatic inheritance of its coastline in the early 1990s, is looking to redress what Prime Minister Ahmed calls a ”geographical anomaly”. The deal with Somaliland was struck with that in mind.

Following several mediation efforts by Turkey, the authorities in Addis Ababa appear to have softened their tone, and eased tensions with Somalia, but the sense of mistrust runs deep and fuels closer rapprochement between Mogadishu and Cairo.

Red Sea’s trade value

The value of the Red Sea to the global economy is well documented and represents one of world’s busiest shipping lanes. The route which shortens the trip for trade ships between Asia and Europe and beyond accounts for 12 percent of maritime commerce and 30 percent of container traffic. The alternative route is skirting around Africa through the Atlantic Ocean which is twice as long as access through the Red Sea. Over periods spanning six decades, this body of water which in ancient times was known as the Erythrean Sea has also gained a reputation as an international touristic hub with notable resorts such as Sharm-el-Sheikh on the Egyptian shore, Jordan’s Aqaba and Eilat in Israel referred to as the Red Sea Riviera.

It was an important part of the trade in spice during the Middle Ages and this significance has never been lost in modern times, leaving Ethiopia desperate for a slice of the lucrative commerce it offers her riparian neighbours.

Dr Terrefe writes that Ethiopia views the development of new ports, particularly Berbera and Assab, as an alternative to the ones in Djibouti which will reduce logistics gap for the landlocked country and facilitate economic integration and progressive relations with its neighbours.

”Abiy frames this as matter of national necessity, driven by demographic pressures and the need to secure peace, prosperity, and stability. He further ties this to historical claims and the shifting dynamics of regional geopolitics” writes the author whose previous works have appeared on the Washington Post and The Economist.

He says the idea of Ethiopia as a ”regional and global superpower” takes inspiration from a glorious past, drawing parallels with Axum and Ifat, two kingdoms both of which enjoyed access to the Red Sea.

According to Abiy’s Red Sea doctrine, Ethiopia’s ambition is for the long term and by then discussion, dialogue and new narrations may generate new insights including from the nations with access to the sea.

MG/as/APA