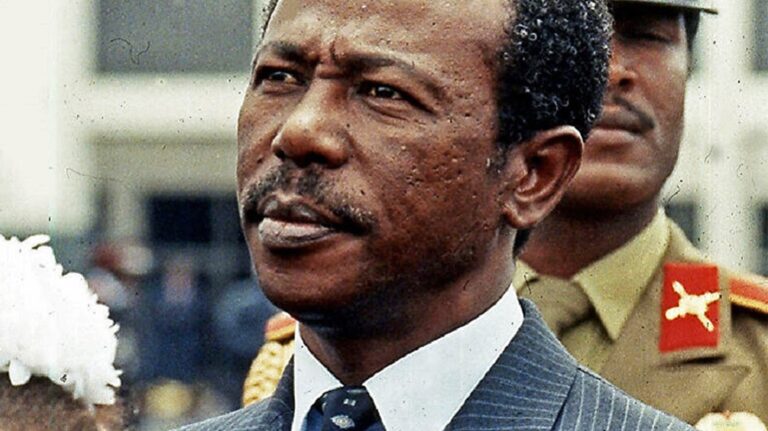

Has time and circumstances remained kind to Ethiopia’s deposed former military ruler Mengistu Hailemariam?

He holds the record for being the deposed former African head of state with the longest years in exile.

Chad’s ex military strongman Hissene Habre who died in Dakar, Senegal in August 2021 after spending 31 years in exile in the West African country following his overthrow in 1990 held this distinction.

The military ruler of Ethiopia from 1977 to 1991 seems to be soldiering on in exile in Zimbabwe apparently forgotten by the rest of the world given the enormity of the alleged crimes his DERG regime are held responsible for during this period in Ethiopian history.

Since his overthrow in the early 1990s, Mengistu, now 87has defied attempts to either assassinate him or bring him to justice for what many Ethiopians regard as one of the darkest chapters in their ancient history known to the world as the Red Terror years.

Mengistu was an esteemed guest of late President Robert Mugabe for decades but continues to be heavily protected and enjoys a life of staggering opulence under former Mugabe protege Emmerson Mnangagwa.

Over three odd decades have passed since Mengistu was surreptitiously flown into exile in Zimbabwe, but the veil of secrecy which had characterised much of his life outside of Ethiopia since then has not showed any sign of lifting.

Nothing tangible is known about him other than a failed assassination attempt in 1996, a burst of unsuccessful bids to extradite him to account for the Red Terror, his fight against a heart disease which prompted a medical sojourn to South Africa in 1999 and the noise generated around more calls for his extradition which Pretoria had rebuffed.

After this there has been stone silence about him and even trails that could have led to the man and offer helpful glimpses about his life had gone wearily cold. All that the rest of the world knows about him are tit-bits about the protective rings of security around him wherever he is. Members of the Zimbabwe intelligence community have never been in the mood to take chances with his security since a would-be assassin missed him by a hair’s breath while strolling on the streets of Harare. It later turned out in court in Zimbabwe that the shooter had wanted to exact revenge on Mengistu for sanctioning his torture as was the case when detainees were held by the DERG.

During the Mugabe years, Mengistu assumed something of a public life as a government adviser on security policy in the southern African nation. Sources say Mengistu even went as far as chairing meetings in the lead up to highly unpopular Operation Murambatsvina in 2005 to rid the country of illegal housing nationwide. The operation drew strong criticism from all strata of Zimbabwe society especially slum dwellers hundreds of thousands of whom were adversely affected either through the loss of homes of livelihoods. However, some in Mugabe’s regime had denied that Mengistu had had any hand in orchestrating the operation.

Rights activists have not reached a consensus over how many people may have been killed during the Red Terror in Ethiopia as Amnesty International estimated the figure to be around 500, 000 while others put it much higher. Eyewitness testimonies after his fall suggest that the mass murder of political opponents included student critics of the regime, or rebels and their sympathisers who were left hanging from street poles as a warning to would-be detractors.

He was also under fire at the time for reportedly turning a blind eye on over 1 million of his own people who fell from cataclysmic famine which blighted Ethiopia between 1984 and 1985, prompting the world to act as epitomised by the Band Aid efforts to raise money and assuage mass starvation in the country.

In 2022, the government of President Mnangagwa who succeeded Mengistu’s late protector Mugabe, hinted it might accede to calls for the former military leader’s extradition where he was sentenced to death in absentia for genocide.

Since then there has been no word on Mengistu from the authorities in Harare who seem to accord the same privileges to the scrawny old man from Ethiopia who many believe left his own indelible personal imprint on the massacres of the 1970s and 80s.

A Zimbabwe analyst whose identity is being protected by APA over the sensitivity of the subject, says the former dictator’s extradition case is a significant example of the complexities involved in seeking justice against former African rulers who had hurt their nations while in power.

Despite being convicted of genocide in absentia, the Zimbabwe government continues to regard him as worthy of their protection although from a political point of view this could change, the anonymous commentator said.

In a notable policy shift, former Zimbabwe Foreign Affairs Minister Frederick Shava announced in 2022 that Harare is ready to extradite Mengistu.

“If the people of Ethiopia approach the government of Zimbabwe, appropriate steps will be taken by the Government of Zimbabwe in response to the request, to the legitimate request from the government of Ethiopia,” Shava told journalists at the time.

Ethiopia has not made any attempt publicly to seek Mengistu’s extradition since then.

The government in Addis Ababa is all too preoccupied with matters that are more existential to it than pursuing a former crackpot dictator, now almost incapacitated by advancing age and still living in tight seclusion and not poking his nose on Ethiopian affair.

A high-placed source told APA in the Ethiopian capital that both governments in Addis Ababa and Harare consider the extradition of Mengistu as not a very important and attractive proposition for the two countries. In 2018, then Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn posted on his Facebook page a photo of himself with the Marxist-Leninist ex leader before quickly taking it down after it stirred controversy. But the message implicit from this could not be denied that a smiling Desalegn next to Mengistu was indicative of cozying up to the man instead of bringing him to justice.

But Shava’s announcement marked a departure from Zimbabwe’s previous stance, as articulated by the late former Information Minister Tichaona Jokonya in 2009, who said Harare would not extradite Mengistu, citing his status as a refugee under the United Nations convention.

This case highlights several key issues in the pursuit of justice for former dictators.

Our analyst in Harare says Mengistu’s continued residence in Zimbabwe, despite the issue of his extradition being open, underscores the challenges of political asylum.

”Countries that offer refuge to former leaders often do so for political reasons, complicating efforts to bring these individuals to justice” he adds.

Fleeing dictators often seek asylum in countries that they know would always protect their interests, and, therefore, can guarantee their security from prosecution.

Similarly, Mengistu’s case demonstrates how international relations and diplomatic considerations can impact the pursuit of justice.

”Zimbabwe’s initial refusal to extradite Mengistu, even under pressure from Ethiopia and other international bodies, reflects the delicate balance between national interests and international justice” the anonymous commentator observes.

Mengistu’s case raises important questions about the legal mechanisms available to hold former dictators accountable.

The lack of a consistent international legal framework for extradition and prosecution of such individuals often results in prolonged impunity.

Will the authorities in Zimbabwe hold firm over Mengistu or will changed circumstances force their hand towards extraditing one of the last remaining exiled dictators of old who has lived below the radar of international justice for too long?

WN/as/APA