Groundbreaking archaeological discoveries at Oued Beht, Morocco, reveal a sophisticated agricultural society from 3400 to 2900 BC, rewriting the prehistory of the Maghreb and the ancient Mediterranean world.

A major archaeological discovery in Morocco is shedding light on the prehistory of North Africa and its role in the ancient Mediterranean world.

The Oued Beht Archaeological Project (OBAP), a collaboration between researchers from the UK, Italy and Morocco, has uncovered evidence of an advanced agricultural society that flourished between 3400 and 2900

BC.

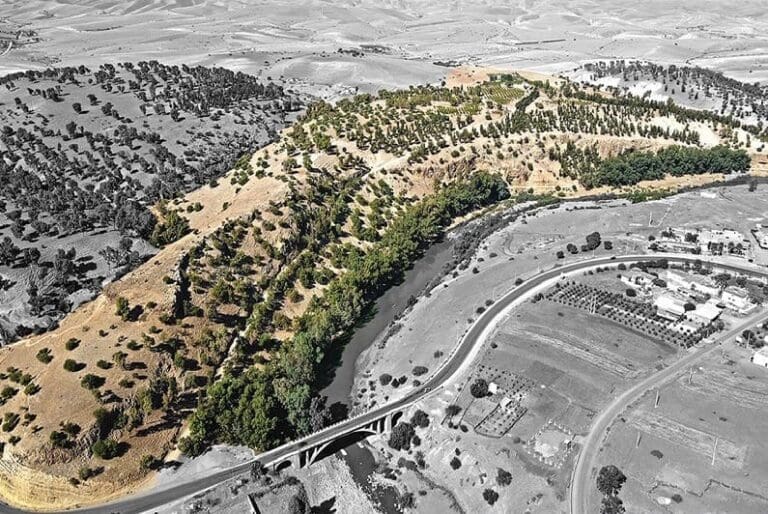

Located on a ridge overlooking the Oued Beht River, the site was first identified in the 1930s based on its abundance of prehistoric stone artefacts. It was only in 2021 that the OBAP team, led by Professors

Cyprian Broodbank (University of Cambridge), Giulio Lucarini (National Research Council of Italy) and Youssef Bokbot (National Institute of Archaeological Sciences and Heritage, Morocco), undertook intensive excavations.

Radiocarbon dating of charcoal and seeds indicates a prosperous occupation in the late fourth or early third millennium BC, a period known as the “Final Neolithic”. This period remains one of the least understood chapters in regional prehistory.

Surface studies using advanced techniques such as drone photogrammetry and geophysical prospecting have revealed the scale of the ancient settlement, covering 9–10 hectares. “The concentration of pottery and lithics at Oued Beht is unprecedented at this date on the African continent outside the Nile corridor,” the authors write in the journal Antiquity.

The excavations revealed numerous deep bell-shaped pits, likely used for storing cereals, such as barley, wheat, and peas, confirmed by carbonized remains. Faunal remains show a reliance on domestic sheep, goats, cattle, and pigs, with little evidence of exploitation of wild resources.

The researchers note that “the untapped potential of the late prehistory of the Maghreb is illustrated by this modest-sized pit, which has produced the most reliable evidence of agriculture in the region for nearly two millennia.” Oued Beht’s material culture, including finely worked pottery and stone tools, attests to the sophistication of this society.

One intriguing discovery is a tradition of black-on-white painted pottery, rare in the region, but similar to ceramics from the southern Iberian Peninsula. The researchers note the importance of viewing Oued Beht within a framework of Mediterranean connectivity, while recognizing its African specificity.

The Oued Beht discoveries open a new chapter in the understanding of ancient North African societies. The OBAP team is continuing its research to shed more light on the emergence and decline of this remarkable site.

According to Cyprian Broodbank, these discoveries show that the Maghreb played a crucial role in the late prehistoric Mediterranean.

“For more than 30 years, I have been convinced that Mediterranean archaeology has missed something fundamental in the late prehistoric period of North Africa,” he said. “Today, we finally know that this was true and we can start to think in a new way, recognizing the dynamic contribution of Africans to the emergence of early Mediterranean societies.”

The team concludes: “Oued Beht and the north-west of the Maghreb will now occupy an integral and revised place in the prehistory of the Mediterranean and Africa, long overlooked.”

RT/ac/fss/GIK/APA