Malians are wondering about the future of their country since the army’s announcement on Tuesday that the head of state and his prime minister have been ousted.

By APA special correspondent Lemine Ould M. Salem

It is nine months ago since the military last intervened in Malian politics.

At this same place on the rock-strewn road leading to Badalabougou, a middle class district of the capital Bamako, there is a so-called ‘Grain’, a traditional meeting place where Malians of the same generation converge in the afternoon to discuss burning issues of the day.

One Cheik Togo said he was not interested in the military coup that had just overthrown President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita (IBK), who had been democratically reelected two years earlier.

A day after the new putsch was announced on national television, the young man still claims to indifference to this latest twist in Mali’s political upheavals.

“All Malian people in power are the same, whether they are civilians or military. They are all caimans; they swim and eat in the same pool,” says an employee in a small inn located just next door.

He says his only interest is ‘condiments,’ an allusion to his ‘daily food,’ which is “the only real issue” that the majority of Mali’s 18 million people are bothered about.

In this former French colony, two and a half times larger than France, the new crisis is, according to the young man, “all but one more step” towards the normalization of political life in the country deeply troubled by a brutal jihadist insurgency, which has been raging for nine years.

The conflict has drastically reduced the territory under the control of the Malian state.

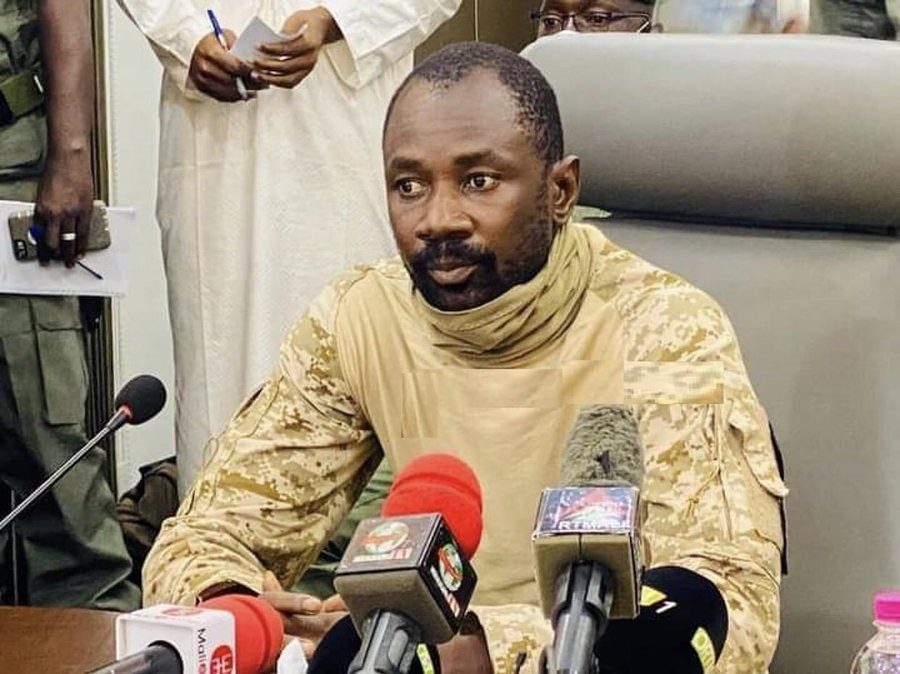

According to a statement signed by Colonel-Major Assimi Goita, the leader of the junta that overthrew IBK in August and also vice-president of the transition that was tasked with restoring “constitutional order,” the army were dispensing with the services of President Bah Ndaw and his Prime Minister Moctar Ouane.

In a statement read out by an officer in uniform on national television, whose broadcasts had been suspended for several days due to a strike that paralyzed most of the public service, the officer, who now assumes the function of head of state, accuses Bah Ndaw and Moctar Ouane of a “proven intention of sabotage” and “violation of the transitional charter.”

Through his statement, he arrogates himself the right of scrutiny over the composition of the government, particularly at the level of the functions of ministers in charge of defense and security issues.

The dispute over these two very important positions (Defense and Security) is one of the main triggers of the new putsch.

The prime minister who had been reappointed ten days earlier, after the resignation of his first cabinet on Monday made public the list of new appointess to a new government from which two colonels, Sadio Camara and Modibo Kone, previously in charge of Defense and Veterans Affairs and Security and Territorial Administration, were excluded.

The two men are close allies of Colonel-Major Assimi Goita, who absolutely wanted them to keep their positions.

Whisked away to the military barracks in Kati, the president, his PM and some of their allies were still held incommunicado on Tuesday afternoon.

“The situation had been tense for some time. The differences over the composition of a new government were so deep that some of the military wanted the outright departure of Prime Minister Moctar Ouane. The dismissal of the two officers from the ministries of defense and public security in the new cabinet announced by the Prime Minister on Monday triggered the crisis” says Bokar Sangare, a young researcher and also one of the most brilliant analysts in the country.

According to him, the military wanted at all cost to win the game, even if it meant using secondary means, such as the social climate.

“Already in December, a first strike by the country’s main trade union association, National Union of Workers of Mali (UNTM), was called,” the researcher says.

An agreement with the government had been signed, but its implementation suffered delays which led to a new strike in mid-May, which was finally suspended Tuesday evening in the wake of the ousting of the latest coup.

In the statement made on Tuesday morning, Colonel Assimi Goita also referred to this situation, even though it was not necessarily decisive in his decision to dismiss the two men.

“It’s too bad that we have to go through this situation. Serious challenges lie ahead for the country. This is a big blow to the transition. Mali is in danger of further divisions while it still faces an ever-worrying jihadist threat,” his colleague Mohamed Maiga laments.

The teacher-researcher in the Social Sciences and director of the consulting firm, Aliber takes with a pinch of salt Goita’s promise to respect the electoral calendar which is supposed to lead the country to the election of a new parliament and a future president in 2022 at the latest.

Los/fss/as/APA