They are wondering about the harmful consequences that this extraction could have on the marine ecosystem,

which is their main source of livelihood.

The rancid smell of rotting fish entrails tickles the nostrils. Here and there, young people load goods of all kinds onto carts to be transported to the traditional boats moored a little further away. Under makeshift tents, women are busy serving breakfast, while others are making their last purchases in nearby stalls. Everyone is too busy. No one is paying any attention to us. We, on the other hand, have to be careful not to slip on the slimy water that has oozed out of the tubs and other containers used to collect or preserve the fish.

Welcome to the fishing quay at Missirah Niombato, a village in the commune of Toubacouta, some 240 kilometres south-west of the Senegalese capital, Dakar. “Hurry up! We’ve got to get there before

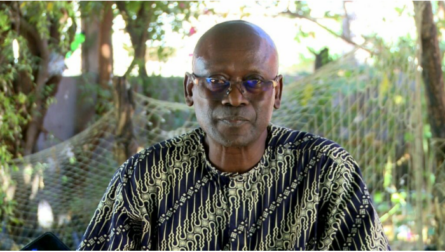

the tide goes out,” the pirogue driver says. “Take your time! The tide won’t go out again straight away,” reassures Alassane Mbodj, departmental delegate for the Local Artisanal Fishing Council (CLPA) in the district of Foundiougne.

On the morning of Thursday 28 December 2023, the weather was fine and the sky was clear. On the horizon, the sun illuminated the sea with an orange hue. A light breeze is blowing from the west, with the temperature hovering around 23°C. Humidity is moderate. No risk of rain or thunderstorms.

In short, the ideal weather for setting sail for the island of Bossinkang. Accompanied by Alassane Mbodj, the visitors boarded the CLPA pirogue from Missirah Niombato.

After a short crossing, they enter the mangrove forest. Its roots, like tentacles, sink into the mud, forming labyrinths where the currents weave their way through. The sun filters through the branches, casting a subdued light on the gnarled trunks and dark green leaves.

Birds chirp in the trees. Fry swim in a silent ballet in the murky waters. A dazzling wild beauty. The pirogue glides slowly. You can hear the sounds of life teeming around you, smell the scents of the sea and the land kissing.

This mysterious and enchanting world, where nature reigns supreme and time seems to stand still, is a world apart. It’s a place where paths cross, directions get lost and landmarks disappear. A place where you

can lose yourself and find yourself again. A place where you can dream and let your imagination wander.

“We are in a resting area, a breeding area, but also a protected area. Everyone in the fishing industry depends on this environment. That’s why it’s respected and protected. The players themselves are taking care to reforest all the pockets that are being emptied because of the harmful effects of climate change,” Mr. Mbodj explains.

An invaluable ecosystem

These Bolongs (channels) are part of the Saloum Delta. This natural region extends over 180,000 hectares between the Saloum River and its tributary, the Sine. Classified as a biosphere reserve by the United

Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO), the Saloum Delta is home to an exceptional ecological wealth of mangroves, lagoons, forests and sandbars. It is also the main source of income for more than 100,000 people, who make their living from fishing, shellfish gathering, bee-keeping and tourism.

According to a study entitled Evaluation of the Sustainable Assets (SAVi) of the Saloum Delta in Senegal, carried out in 2020 by several organisations including the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD), the value of the ecosystem services of the Saloum Delta “amounts to 964 billion CFA francs (€1.5 billion), and the value of the income from work directly generated by the ecosystem reaches 1973 billion CFA francs (€3 billion) over a period of 10 years.”

The same source adds that “the value of ecosystem services increases to 3,589 billion CFA francs (€5.4 billion), and the income from work generated increases further to 9,729 billion CFA francs (€14.8 billion) over a period of 40 years.”

It is off the coast of this fascinating but fragile ecosystem that oil will be extracted this year from the Sangomar Offshore field, the geographical name of an island in the Saloum Delta National Park. It’s a prospect that has local residents worried.

“People are not being responsibly informed about the imminent exploitation of the Sangomar offshore field. Of course, they know that exploitation will take place, but they cannot say anything more than that. So far, the information remains at the level of Woodside and the State. Not everyone is informed, although they should be. No one should be taking decisions on behalf of others, or making proposals on behalf of a fisherman who is there and whose only activity is fishing,” says Alassane Mbodj.

The departmental delegate also condemns the fact that local people were not involved in the project from the outset. “There was no community involvement during the environmental impact studies. Admittedly, some leaders are sometimes invited to take part in workshops or seminars dedicated to the project. But unfortunately they do not always give feedback to the communities. What’s more, these studies seem to be mere literature. There’s no point in inviting “illiterate” people and giving them documents they cannot read. What good will it do them?” he asks, urging the joint venture between Woodside (the operator) and Societe des Petroles du Senegal

(PETROSEN) to get closer to the communities to find out what their concerns are.

On its website, the Australian company claims to have held more than 60 community consultations. “I took part in a few workshops organised by Woodside. However, the company does not give clear details of its plans for local content and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). The company has not provided communities with a clear roadmap. Nor has it presented anything in the way of alternatives or compensation, particularly with regard to fishing activities in the event of problems,” adds the departmental delegate of the Local Artisanal Fishing Council (CLPA) in the district of Foundiougne.

About 40 minutes have passed since we left the landing stage at Missirah Niombato. A few more minutes by pirogue and Bossinkang is revealed like a postcard. On the beach, multicoloured shells sparkle in the sunshine. At the water’s edge, pretty, colourful pirogues are neatly lined up, ready to go fishing. In the distance, generous

coconut palms sway gently in the breeze, offering shade and fruit to locals and visitors alike.

Oil exploitation is causing anxiety in the fishing industry

Bossinkang Island is not just a place to relax, it’s also a place to live. Under wooden or tin huts, women are busy washing clothes and chatting. A little further on, small groups of young people chat over teapots. Under the shade of cashew trees, men weave fishing nets with skill and patience. Their precise movements are synchronised.

Not far away, carpenters, heirs to ancestral know-how, build wooden pirogues. They carefully carve, assemble and paint the boats. This calm life, with its peaceful air, contrasts with the concern of the local people about the imminent oil exploitation in the area.

“We cannot prohibit this development because the state has already made commitments. Of course, it’s for the good of Senegal, but the government must also think of us who live alongside these deposits. If there is a problem, our very existence will be called into question,” warns El Hadj Dianoune Sonko, the village chief.

Still in the grip of his fears, the chief adds: “On these islands, everyone lives from fishing. It’s our only source of income. The men are fishermen/fishmongers and the women gather, process and sell fish products. Our whole lives revolve around this ecosystem, and oil exploration is likely to make fish even scarcer. Worse still, we fear

the disappearance of certain species that are already rare in the event of marine pollution.”

Even though exploitation has not yet begun, Mr. Sonko is already looking ahead to its long-term consequences. “Some people say that we are a long way from the exploitation zones, but no matter how far away we are, sooner or later the consequences will be felt. There is no natural or artificial barrier between the oil field and the islands.

And that makes us vulnerable to any spill or accident. The government needs to start thinking about alternative activities so that we can continue to live,” he goes on to say.

The results of the study by IISD and its partners show that “oil extraction generates significant revenues, but also has a high negative impact on the ecosystem services provided by the wetlands and mangroves of the Saloum Delta.”

The marine ecosystem is home to exceptional biodiversity, essential to the survival of communities. Any unfortunate event could therefore affect people’s food security and health. “We fear that offshore oil

exploitation will destroy the mangroves, leading to the disappearance of fish, molluscs, clams, etc. If this happens, we will suffer the consequences. Because the sea is our only resource,” laments El Hadj Mamadi Diouf, a fisherman from Bossinkang.

Concern, a constant on the islands

A negative impact from oil exploitation would also have fatal consequences for the 300 or so women who gather, process and sell fish products in Bossinkang.

“In a four-day tide, we can earn between 30 and 40 thousand CFA francs (45 to 60 euros). With this money, we can support ourselves and our children. The most important thing for us is that this exploitation has no impact on our activities. Otherwise, our lives will be affected,” says Nafi Diouf, who is preparing to set sail.

The sun is already high in the sky. It’s time to set sail for Bettenty Island, just a few kilometres away and not far from Bird Island. This seven-kilometre strip of land is a veritable jewel of nature. “This island is a resting place for many species of birds, including pelicans, pink flamingos and cormorants, which come here to spend the

winter,” the guide explains.

Like its peers, this island paradise, close to the Gambia and home to around 12,000 people, is home to a community of fishermen living mainly from traditional fishing. Like the other islanders, the people

of Bettenty are concerned about the risk of pollution and environmental destruction from oil drilling. Fear is written all over their faces whenever the subject is raised.

“Oil production can only have a negative impact on mangroves. Experiences reported elsewhere are hardly reassuring. Oil is certainly a financial windfall, but there’s a disaster aspect to it that we can’t rule out,” laments Bakary Mane, a development worker in Bettenty.

The effects are already being felt

According to Mr Mané, the Saloum Delta is a zone that absorbs a certain amount of water from the oil exploitation zone. As a result, he continues, everything that is thrown into the open sea ends up on

our beaches. “As proof, we collect bottles of water and other products that, according to some reports, come from the platform. We’re really scared. Especially as the mangrove is vital. It’s what sustains us,” he says.

“Since the oil platform was installed, the fish have diminished considerably. We can spend 24 hours at sea and not fill a single box. Today, we sometimes don’t even have enough to cook. In the old days, we could have 10 or even 20 crates of fish. So we’re starting to feel the effects, and I fear that the sea will soon be empty. People are so afraid that some have immigrated,” says Ibrahima Bodian, a fisherman from Bettenty.

However, the problem of the increasing scarcity of fish in Senegal does not date back to the discovery or installation of oil platforms. For some years now, small-scale fishermen have been blaming foreign trawlers for their plight. However, unusual phenomena have attracted the attention of many during the drilling of exploration wells in the Sangomar field.

“Today, people are talking about the risks of oil leaks and oil spills. A few years ago, cetaceans washed up on several beaches. No scientific study has proved that this was linked to oil activity. But based on our knowledge of the environment and our experience, we thought that before this seismic research, there were no whales

beaching themselves. So we’re wondering,” says Bakary Mane.

It’s past 1pm. The sun is beating down on the sky, beaming down on the loamy earth left by the tide. This is the time chosen by the women of the village to set off to gather clams, oysters and other shellfish. Aware that they only have a few hours before the tide comes back in, in small groups, buckets, baskets and other tools in hand or on their heads, they set off at a determined pace towards the pirogues waiting for them a little further down.

Life jackets are not left behind. Bettenty is still scarred by the tragedy of 25 April 2017. On that day, a pirogue carrying women returning from picking oysters capsized due to a heavy swell, killing 21 people.

Fatou Diouf, whose main business is selling fish products, is eagerly awaiting the return of her sisters from the sea. She is not hiding her concerns either. “Won’t oil exploitation destroy the sea? That’s the only question the women are asking themselves. The sea is still our main source of income. Unfortunately, we are suffering the

consequences of restricted access to certain areas recently included in the marine protected areas,” she recounts.

Local initiatives to guard against any eventuality

The day is drawing to a close. The tide, which had receded from the shore, is slowly returning. The sun, like a huge globe of fire, plunges into the ocean, flooding the sky with flamboyant colours. The deep blue sea is transformed into a mirror with golden reflections. The air is charged with the scent of the sea.

The women, who had gone out to harvest fish, return, crossing the sunset like luminous silhouettes. It’s time to go ashore. Here too, the issue of oil exploitation is at the heart of the concerns.

“We wanted to anticipate any criticism that might be levelled at oil production in the Saloum Delta. Indeed, it is common to hear that it is leading to the disappearance of certain species. That’s why we launched a scientific study to determine the potential of our ecosystem prior to oil development. The study looked at resource

mapping, village profiles and resources at risk. The results, which will be published shortly, will provide information on the current state of the Delta ecosystem. They will also serve as a tool for easuring the impact of this exploitation on the environment,” points out Moussa Mane, head of the Niombato FM community radio station in Soucouta in the commune of Toubacouta.

Anxious to preserve their source of income, local players, accompanied by NGOs working to protect community rights, are stepping up initiatives to raise awareness of oil exploitation and its possible repercussions on the marine ecosystem, and to raise their voices so that their concerns are taken into account by decision-makers.

They are supported in their efforts by community radio stations, including Niombato FM. ‘At local level, we have taken the lead in raising awareness among local people to help them understand the issues surrounding oil. We’ve broadcast a lot of programmes and spots talking about Woodside and its activities. But I don’t think people are well enough informed. Passing on information is one thing, but getting people to understand what’s at stake in oil itself is quite complicated because it’s something that’s very new to us,” Mr. Mane says.

He believes that “ideally, if possible, we should sign contracts with all the community radio stations in the Saloum Delta and organise public broadcasts where we can be as close as possible to the people and try to take their expectations into account.”

These include setting up alternative training programmes for fishing activities. But also a revision of the law on local content. “The people of the Saloum Delta don’t see themselves in local content as it is currently defined. No one has the necessary qualifications to apply for a job in a company linked to oil exploitation. There are no local

skills that could be used for local content. So we’re calling on the government to make a few changes to the way the oil windfall is distributed, by earmarking part of it for the development of the Saloum Delta,” Bakary Mane further says.

Oil production at Sangomar has once again been postponed until mid-2024. This ambitious project, with estimated reserves of around 630 million barrels of crude oil and 2.4 TCF (113 billion cubic Nm) of natural gas, has the potential to generate significant revenues for Senegal. The revenue expected from the exploitation of hydrocarbons from the Grand Tortue Ahmeyim (GTA) gas field (on the maritime border with Mauritania) and the Sangomar oil field over the three-year period is estimated at a total of 753.6 billion CFA francs, according to the

Multiannual Budgetary and Economic Programming Document (DPBEP 2024-2026).

ARD/ac/fss/abj/APA