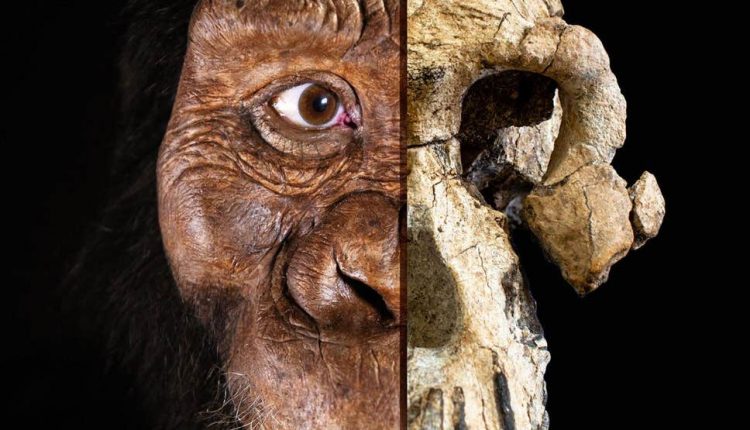

Scientists have recreated the face of an early human ancestor after a “remarkably complete” skull dating back 3.8 million years was discovered in Ethiopia.

Researchers on Wednesday said the find at the Woranso-Mille palaeontological site was a “game changer” in the understanding of human evolution.

The fossil, referred to as MRD, was found in the Afar region of Ethiopia in February 2016 and represents a time interval between 4.1 and 3.6 million years ago when such fossils are extremely rare.

It sheds new light on what Australopithecus anamensis, a species widely accepted to have been the ancestor of Australopithecus afarensis, represented by the famous Lucy fossil – look alike.

MRD also shows that Lucy’s species and its hypothesised ancestor, A. anamensis, co-existed for around 100,000 years, challenging previous assumptions of a linear transition between these two early human ancestors.

Cleveland Museum of Natural History curator and Case Western Reserve University adjunct professor, Dr Yohannes Haile-Selassie, said: “This is a game changer in our understanding of human evolution during the Pliocene (epoch).”

The earliest members of the hominin genus Australopithecus have remained poorly understood, because of the near absence of cranial remains older than 3.5 million years.

Dr Yohannes and colleagues assign the cranium to A. anamensis on the basis of its teeth and jaw.

It is likely to be an adult male despite its small size.

However, scientists say the primitive cranial morphology links this fossil to even more ancient hominins, such as Sahelanthropus and Ardipithecus, and casts doubt on previous assumptions about a direct link to the younger Australopithecus afarensis.

Co-author Dr Stephanie Melillo of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany, said: “A. anamensis was already a species that we knew quite a bit about, but this is the first cranium of the species ever discovered.

“It is good to finally be able to put a face to the name.”

She added: “We used to think that A. anamensis gradually turned into A. afarensis over time.

“We still think that these two species had an ancestor-descendent relationship, but this new discovery suggests that the two species were actually living together in the Afar for quite some time.

“It changes our understanding of the evolutionary process and brings up new questions – were these animals competing for food or space?”

Dr Yohannes said that one of the reasons the finding was so significant is because this is the “first specimen that gave us a glimpse” of what the face of the species looked like.

He added that, while the idea of Australopithecus afarensis being the ancestor of Homo had not been falsified yet, this finding suggests there could be other answers.

A separate paper also published in the Nature journal, describes the age and context of the cranium, and suggests the hominine lived in predominantly dry shrubland, with varying proportions of grassland, wetland and riverside forest.

MG/as/APA